What’s the Deal With Micro mobility?

With due respect to that Seinfeld signature opening, what is in fact is the deal with micro-mobility?

It’s not hard to find negative press on micro-mobility products such as spent rental e-scooters littering city streets, e-bike riders zipping among traffic or on sidewalks, or media stories highlighting the novelty of powered skateboards. Mobility advocates push and lobby for incentives to attract users. Others however, would argue it’s at the expense of sensible product monitoring, licensing and operator training. There has been the expected backlash and resistance with the usual rocky relationships that dot the transportation landscape. New players tend to disturb an already stressed system.

The various levels of government have moved cautiously. An early challenge is to first sift through some definitions around micro-mobility.

First, start with the view of the U.S. Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) who weigh in with the idea of classifying “micro-vehicles”. The SAE distinguishes six types of powered micro-vehicles:

1. powered bicycles

2. powered standing scooters

3. powered seated scooters

4. powered self-balancing boards

5. powered non-self-balancing boards

6. powered skates

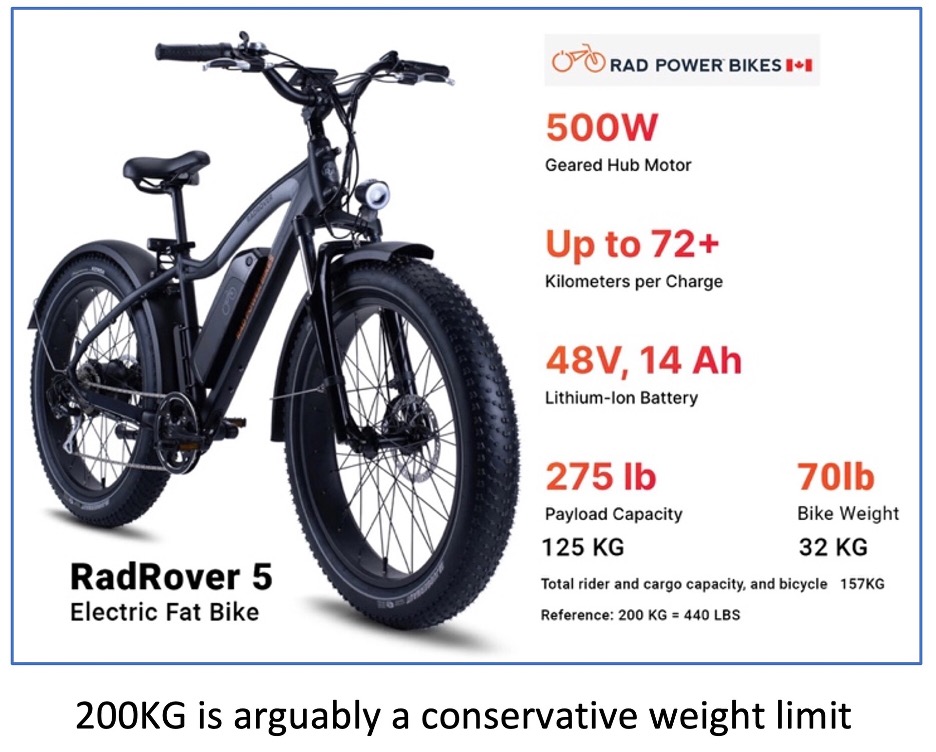

Next, is how big is “micro”? A vehicle “weight cap” is still looking for consensus. It’s an important safety and liability aspect since the overall mass of a vehicle and contents can be an obvious factor determining subsequent potential to inflict personal and property damage. Here are three examples:

• “Mobility Podcast” in the US lobbies for a 500 KG (1,002 lb) limit. That’s half a ton!

• A recent International Transportation Forum report cited a cap of 350 KG ( 771 lbs).

• The SAE Association in the US suggest a cap of 227 KG ( 500lbs)

Finally, there is “Application” or “intended use”. It’s the flashpoint for many discussions and can start with the notion of what micro-mobility isn’t. It’s a pragmatic thought.

Some say these products are unsuitable for sidewalks, which are the domain of pedestrians and certain very-low-speed vehicles. They are also unsuitable for vehicle-occupied roads dominated by cars and trucks capable of highway speeds.

Thus, you end up with the overarching view to say micro-mobility leverages, or is assigned to, bicycle spaces. That is something that can be controlled.

Mobility advocates can glaze over the issues of public interest around safety, legal, and administrative concerns. They focus on incentive messaging similar to what is already realized by motorcycles and scooters; an option to public transit and its Covid concerns, smaller footprint, greener than cars, some personal freedom, and less wear on roadways. However, unlike micro-mobility offerings, motorcyclists need a licence, insurance and training before they jump into the larger transportation system. That’s good for the public interest.

All of this is not to say the powersport industry doesn’t have an affinity to the idea of micro-vehicles. Industry leaders are more likely to cite the view that once people get used to the benefits of two wheels, they want to move up the product ladder. The industry is aware of the pitfalls, as seen in the short clip: Why Electric Bikes Are More Dangerous Than Motorcycles

Always slightly ahead of us,the Motorcycle Industry Association in the UK (MCIA) in their published document “The Route” have added a new Micromobility Regulation: A Discussion Document.

The anchor statement is sound: Micromobility vehicles would appear to offer a publicly acceptable solution to the pressing urban challenges of congestion and air quality. The use (particularly of e-scooters) has already become widespread, albeit illegal. This inevitably raises questions about safety and appropriate regulation.

Their discussion points could translate to the Canadian market:

1. Vehicles should only be eligible for use on roads with a speed limit of 30mph or less

2. Vehicles should have electric propulsion

3. Vehicles should have brakes, steering and lighting which meet an appropriate standard

4. There should be minimum wheel sizes

5. Users should hold a provisional licence

6. Vehicles should be registered

7. In some cases, vehicles should have motor insurance coverage

8. A voluntary training scheme, similar to Bikeability should be established

The above MCIA points are likely a view first responders and police can get behind. There is a growing concern with many mobility products increasingly being part of criminal acts. These products do offer the nefarious some attractive features: often amazing performance, no need to buy from a licensed motor dealer, no registration, no safety gear, and no insurance. In many cases they are cheap enough to just throw away after the job.

The challenge for government and regulatory bodies is to properly incentivise micro-vehicle products, but in concert with current sales regulations, licensing, and safety training – all designed to be in the public interest. In that discussion, the larger powered two- wheel industry is ready to help.